Author of ‘In the Dream House’ speaks out about district censorship

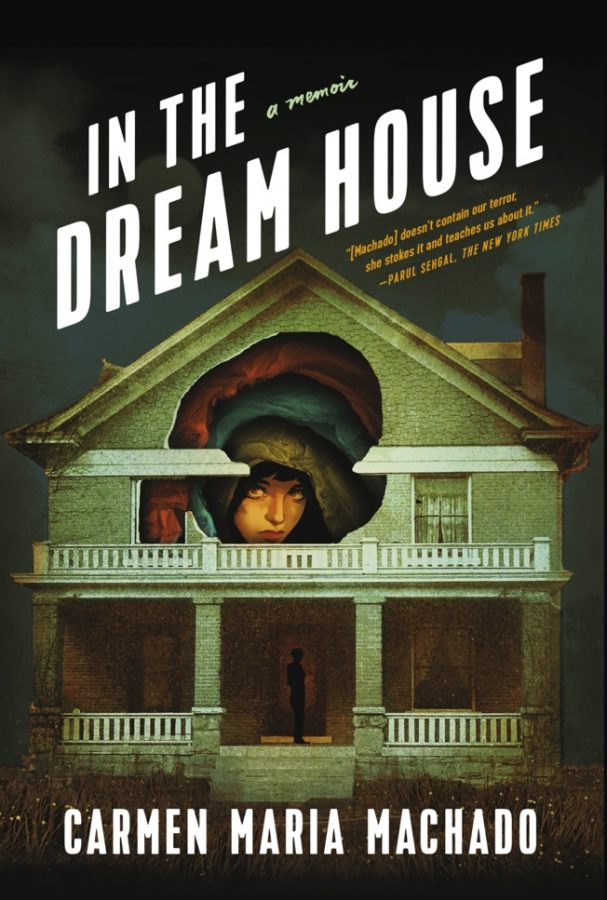

Book “In the Dream House” by author Carmen Maria Machado

April 27, 2021

Several authors including Carmen Maria Machado of “In the Dream House” recently wrote a letter to the district urging LISD to revoke the bans and suspensions of their books.

Other authors who signed the letter include Margaret Atwood (“The Handmaid’s Tale”), Mariko Tamaki (“Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me”), Elizabeth Acevedo (“The Poet X”), Jacqueline Woodson (“Red at the Bone”) and Erika L. Sánchez (“I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter”).

Several of these books have either been removed from district reading lists or are currently being reviewed after months of parent debate about their appropriateness. The ongoing discussion was brought up at the district board meeting on Feb. 25 where parent Lori Hines read an excerpt and complained about explicit content present in book “In the Dream House.”

“In the Dream House” had been on a student book club reading list, as an optional read. After multiple parent complaints, the district removed “In the Dream House” from being an optional read and decided to start a reviewing process of all books in district curriculums and book clubs, and have since removed multiple books from optional use throughout the district.

“I feel like sometimes people forget that this is still a thing,” Machado said. “People talk about censorship and they’re like ‘Oh yeah, that used to happen,’ but it still happens.”

“In the Dream House” is a book that is part memoir, part history. It highlights a time in Machado’s life when she was getting into and getting out of an unhealthy, abusive relationship with another woman. The fact that the relationship was queer is heavily discussed and elaborated on in the book.

Machado said that one of the main themes in the book is what it means to be in an abusive relationship that is also a queer relationship, alongside the history surrounding domestic violence in the queer community and the way people have talked about violence in the past and present.

The main complaints from parents directed at the book were claimed to be because the book involves sexually explicit content, which it does. However, “In the Dream House” isn’t solely focused around sex, but also explores different themes of healthy vs. unhealthy relationships.

“Ideally, we teach kids sex ed, but we don’t teach them relationship ed,” Machado said. “We don’t talk about what an unhealthy relationship looks like, what’s normal. We don’t give people that framework and we definitely don’t give it to gay kids.”

Concepts of how queerness is talked about and how people talk about gender in an abusive relationship, are themes that can be educational and relatable to students reading about them.

“I think it would have meant a lot to me when I was a teenager, just figuring out my whole deal, to have gotten some framework about my own sexuality and what relationships look like,” Machado said. “That would have been very useful for me and I think it would be useful to other people.”

While some parents are in support of the complete removal of these books from school curriculum, others parents argue that they have the right to choose what their children do or do not read and these books should not be banned across the district.

“They’re not professional educators and that’s not their job,” Machado said. “Taking away the ability to read a book that has been assigned by a professional educator from all kids, not just their own children, but from all kids in a district, is horrible.”

Complaints from parent Lori Hines at the district board meeting, and other parents in support of the removal of “In the Dream House” claimed to ultimately support the removal of this book because of some sexually explicit scenes present in the content. However, Machado along with other authors facing their books being removed, have another idea in mind as to why such books have been so thoroughly removed.

“I think that it’s significant that so many books that have been caught in this net of censorship are queer books, are LGBTQ books, and that’s not an accident,” Machado said. “I feel like they’re trying to frame it as sexual. It’s inappropriate, but it’s gay and that’s why you don’t like it. I kinda just wish they would say that. It’s deeply homophobic.”

Though parents have the ultimate right to choose what they want their children to read, Machado emphasizes the importance that parents shouldn’t be able to make that choice for other parents’ children.

“I’m sure they would not want their children to be in a bad relationship and they would want their kid to have a frame of reference for what that looks like,” she said. “They can’t stop their kids from being in difficult relationships, they can’t stop their kids from being gay,” Machado said. “But, they could give them the tools and the abilities to learn about it and talk about it.”

Besides sexual content, other topics like queer representation, the legal history of lesbian domestic abuse, marriage equality and themes of identity, memory and truth present within the book were scarcely mentioned in the complaints, if mentioned at all.

“It’s just really clear that they didn’t read it,” Machado said. “They didn’t understand what they were reading and that’s fine, but that’s also why they’re not professional educators. You have professionals who are making these decisions whose whole job it is to educate children.”

Vandegrift teachers have been asked to stay neutral on this subject. However, Machado said that she has been amazed by so many of the different teachers she has met.

“The teachers I’ve met in this fight have been amazing and made me so happy for all the students because I’ve been like, ‘Wow, what incredible activists. What incredible teachers,’” Machado said. “They’re so brilliant and working so hard to do what’s right by their students. Then, you just have these people who are going up there and being like ‘Gay stuff, sex, etc.’ and it just feels very silly and embarrassing and sad.”