Every minority has experienced the heartwarming feeling of representation. Whether it’s finding your unique name in a math problem, learning about the establishment of your home country in history class, or reading a story whose main character shares your religious beliefs, longing for representation is natural. Problems arise, however, when the representation is portrayed solely through detrimental stereotypes.

In a Texan school like ours, it’s common for students to lack exposure to diverse societies, so it’s immensely damaging when their first discovery of a new culture is depicted in a dreadful light. Specifically, Islamic representation is too often showcased negatively. With an already false media narrative of Muslims across the world as dangerous, controlling people, students may find it easy to believe these blasphemous stereotypes when academic content further tarnishes the religion’s image.

My first encounter with misrepresentation was in World History AP, where students were assigned to read an excerpt of a completely fictitious story of an Arab man who killed his wife. Taking a single character and applying him to an entire faith, students claimed that the story shows how “Muslims were uncivilized” when the teacher asked for their insights.

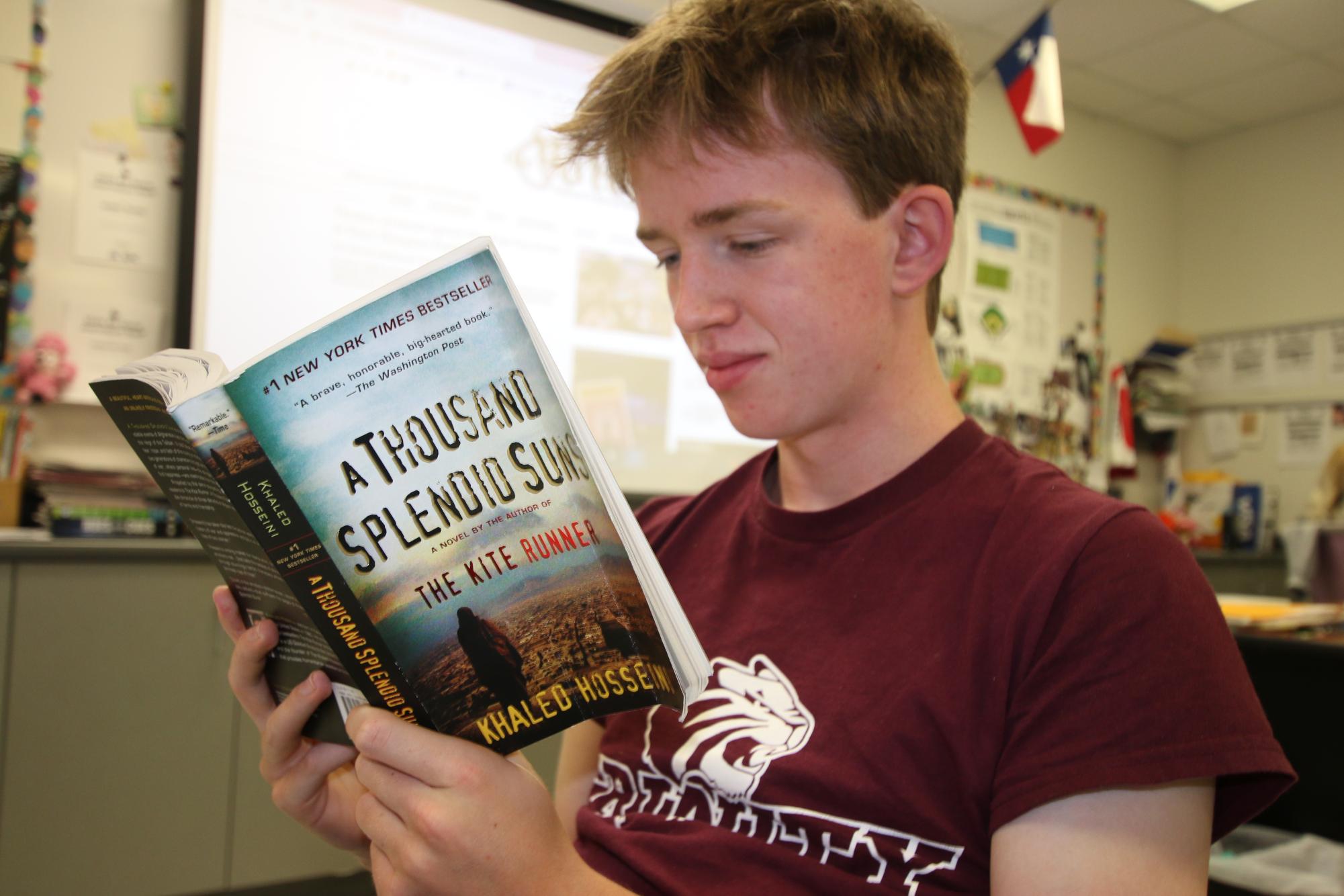

Similarly, AP English Literature and Composition students are currently reading A Thousand Splendid Suns, a historical fiction novel by Khalid Hosseini. This book is set in Afghanistan and tells the story of Mariam, a teenage girl, experiencing a variety of issues including female oppression, child marriage and domestic violence. Throughout class discussions, instead of focusing on the problems themselves, I’ve noticed that students tend to focus on the fact that the corrupt characters are Muslim and Afghan. Hearing whispers around the class like “Of course the abuser’s name is Muhammad” or snarky comments mocking Islamic names in the book only make Muslim students feel more isolated – undermining the very purpose of representation.

AP Literature teachers did encourage students not to fall into these harmful misconceptions. Playing a Ted Talk, The Danger of a Single Story, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, encapsulated how easy it is to neglect the complexity and diversity of a culture when you only see it from one perspective, or in a “single story.” While I appreciate their efforts to prevent discrimination, unfortunately, the racial and Islamophobic microaggressions perpetuate among students.

Books tackling domestic abuse aren’t uncommon. Novels like It Ends With Us by Colleen Hoover and Normal People by Sally Rooney both feature white individuals in their domestic violence stories, yet rarely do I hear anyone bringing attention to their race. If a story centered on white characters doesn’t paint the entire race in a horrible light, then why does a similar narrative but with Muslim characters do exactly that?

Child marriage, misogyny and domestic abuse are all real, pressing matters that the world must be informed on. However, when a single book packs a truckload of issues into the context of one foreign country, people are prone to make generalizations. This is why it’s absolutely necessary for our school to incorporate positive representation into our curriculum. Instead of emphasizing the flaws in Muslim countries that are largely influenced by culture rather than religion, students should be enlightened on the purity of Islam.

I hope future students will get to read novels about the Islamic values of peace, forgiveness and generosity that Muslims embody, rather than a false and twisted version of Islam. This lesson should also be expanded beyond just Muslims, as it applies to all groups that face negative stereotypes. More accurate and positive representation of minorities will not only limit harmful stereotypes, but cultivate a stronger environment for our school in which all students can feel understood and welcome.

Bahia • Oct 14, 2024 at 10:27 pm

Thank you for bringing light to what is wrong in our school curriculum. I appreciate you sharing and I hope you can go forward and reach out to superintendents to educate them.

myreen malik • Oct 14, 2024 at 12:43 pm

the most amazing writer i know❤️🙌🏽

Ayesha Shahid • Oct 13, 2024 at 10:58 am

What a well thought out and captivating article about a much needed discussion. Well done Aisha!

Atique Zafar • Oct 12, 2024 at 4:32 pm

Very important topic and very well written. I completely agree with your commentary and recommendations.